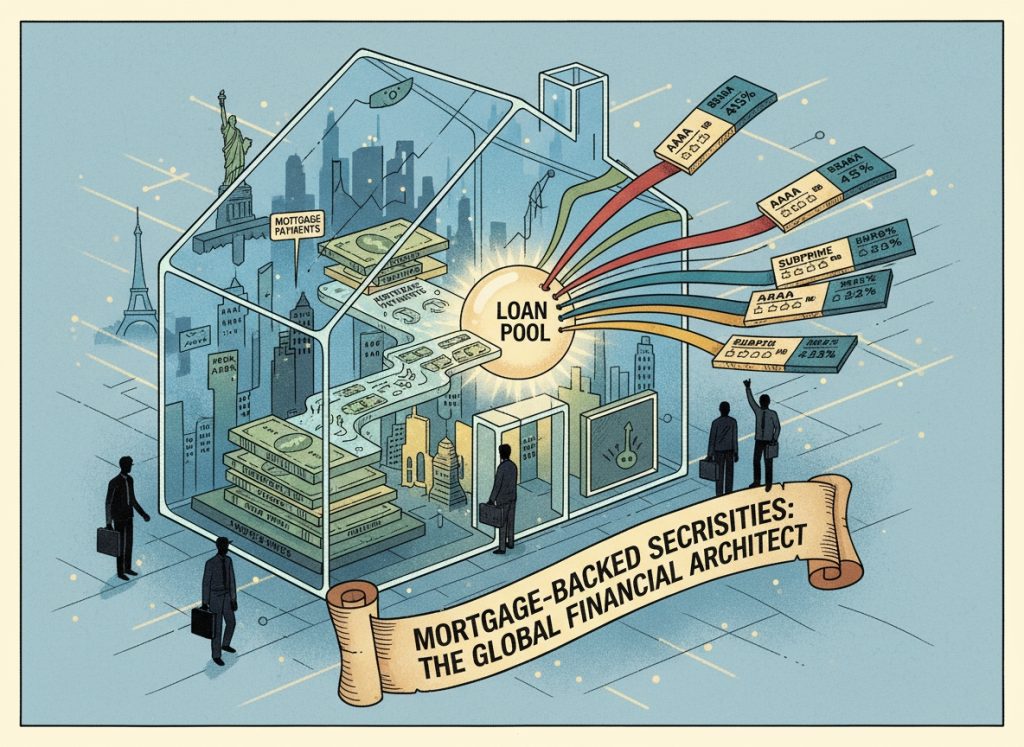

Mortgage-backed securities pool residential mortgage loans and convert the resulting cash flows into instruments investors can buy and sell. That description is simple; the behaviour is not. For traders and allocators the central questions are: how do cash flows vary with the rate environment, how does that affect duration and convexity, and which technical and financing factors can bend prices away from model values.

This article assumes basic familiarity with fixed income concepts—duration, spread, repo financing—and focuses on the mechanics and risks that determine mark-to-market and realised returns. It covers the main product types, how agency markets are standardized through the TBA mechanism, the embedded prepayment option and its valuation consequences, and the practical hedges and financing considerations that professional desks use to manage exposure. Expect fewer platitudes and more of the points that actually matter when you’re sizing a position or explaining a P&L move.

Not copper, how to buy mortgage-based securities. If you’re looking for a broker that allows you to invest in mortgage-based securities, I recommend that you visit day trading.com. They feed you information about brokers that allow you to trade almost any security.

Mortgage-backed securities come in a few distinct legal and cash-flow forms. The differences map directly to what you hedge and what you worry about.

Agency vs non-agency

Agency MBS are issued or guaranteed by government-related entities. Three names dominate: Ginnie Mae (explicit U.S. government guarantee), Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac (GSEs with implicit government support in stressed scenarios). Credit risk for agency paper is negligible for most practical purposes; the dominant exposures are interest-rate path, prepayment behaviour, and delivery/settlement technicals.

Non-agency RMBS (private-label) lack government backing. Investors in those deals underwrite borrower credit, collateral quality, structuring choices and waterfall mechanics. Pricing non-agency MBS is closer to corporate credit analysis: expected losses, recovery rates, structural subordination and tranche attachment/detachment points matter.

Pass-throughs, CMOs and strips

Pass-throughs are mechanically simple: each month servicers collect scheduled principal, interest, and prepayments, deduct servicing and guarantee fees, and pass the remainder pro rata to investors. Cash flows vary with borrower activity.

Collateralized mortgage obligations (CMOs) are engineered from pools of mortgages and split into tranches with different principal payment priorities and exposure to timing risk. A tranche’s value derives from its claim on principal and interest sequences; that makes PACs useful for stable-pay strategies and IO/PO strips useful for expressing views on prepayment direction. IOs (interest-only) and POs (principal-only) have asymmetric sensitivities: IO values collapse when prepayments accelerate, POs gain when principal returns sooner.

Why structure matters

Two securities with identical coupons can behave differently if their pools differ by vintage, FICO distribution, loan balance, geographic concentration, origination channel, or seasoning. Market participants price and hedge those differences. Agency paper lets traders isolate prepayment and convexity effects without embedding credit risk; non-agency paper requires credit overlays and loss modelling.

The trading environment for agency mortgage paper is unique among fixed-income markets. Two mechanisms dominate: the To-Be-Announced (TBA) market and specified-pool trading. Understanding both, and the delivery optionality that connects them, is essential.

The TBA market

TBA is a forward market in agency pass-through coupons. Trades specify issuer (Fannie, Freddie, Ginnie), coupon, settlement month, and price; the particular pool to be delivered is unspecified until shortly before settlement. This standardisation aggregates a wide set of heterogeneous pools into fungible contracts, sustaining scale and liquidity. The TBA market enables forward positioning, hedging, and financing at scale; it is the primary venue for moving agency mortgage risk.

Settlement occurs on fixed monthly dates governed by SIFMA conventions, with notification deadlines for delivery specifics. Because the delivered pool can vary, the seller retains an option to choose among eligible pools, which creates cheapest-to-deliver dynamics discussed below.

Specified pools

Investors who want known prepayment behaviour trade specified pools. These trades settle with identified pools and therefore remove TBA delivery uncertainty. Specified pools often command a “pay-up” (premium) relative to TBAs when their expected prepayment profile is favourable. The pay-up reflects expected lower CPRs (conditional prepayment rates) or desirable seasoning and loan attributes.

Cheapest-to-deliver and delivery optionality

TBA sellers choose among eligible pools; they will typically deliver the pool that is cheapest to them economically, after accounting for accrued interest, coupon, and any pool-level breaks. This creates a spread between generic TBAs and specific pools, and it anchors relative value trades. Dealers and hedge funds routinely model delivery optionality when they arbitrage between TBAs and the underlying cash market.

MBS pricing is not a simple application of yield and spread. Every pass-through embeds an implied option: the borrower’s right to prepay. That option changes both expected cash flows and sensitivity to rates.

The embedded prepayment option and negative convexity

A mortgage borrower’s ability to refinance or prepay produces an asymmetric payoff for the investor. When rates fall, prepayments accelerate—principal returns sooner and reinvestment opportunities worsen. When rates rise, prepayments slow—duration extends and price falls more than a comparable Treasury. The result is negative convexity: price appreciation on a rate decline is limited by faster prepayments while price depreciation on a rate increase is magnified by extension. This creates a convexity short for holders of plain pass-throughs.

Models: CPR, PSA, and scenario simulations

Valuation workflows start with prepayment modelling. Historical CPRs, seasoning curves, borrower characteristics, and economic drivers (rate paths, housing turnover, FHA/GSE program changes) feed a behavioural model. Traders simulate rates under many paths, project cash flows for each path, discount back using a curve and spread, and compute option-adjusted spread (OAS). OAS isolates the spread component after adjusting for option cost; it is the common market shorthand for relative value, but it depends on model assumptions.

Option-Adjusted Spread (OAS)

OAS embeds the market’s consensus view of future prepayment volatility and paths. Two pools with identical nominal coupons can trade at different OAS because of divergent prepayment expectations. Traders watch OAS alongside effective duration and CPR sensitivities; when a pool’s realised prepayments deviate from those assumptions, OAS and market value can shift independently of Treasury moves.

Several distinct risks determine P&L for MBS positions. Understanding how they interact explains why hedging, financing and position sizing are different in this corner of the market.

Prepayment risk (the core)

Prepayments return principal sooner than expected. If costs then the borrower can not be able to receive the interest rate that they had expected to achieve.

Negative convexity and extension risk

Because pass-through holders face negative convexity, they must manage dynamic duration. In a rising rate scenario, expected cash-flow timing extends and duration increases, exposing holders to larger mark losses.

Liquidity and financing risk

Equity can become very poor in down markets.

Credit and policy risk

Non-agency MBS add default and loss-severity risk; tranche structures shift exposures from principal timing to actual principal loss. Agency paper is exposed to policy and legal risk—changes in GSE status, housing finance reform proposals, or Fed MBS operations can move prices. Don’t treat “agency” as an absolute safe-haven if political or policy shifts are plausible.

Operational and settlement risk

TBA settlement mechanics, failed deliveries, and operational mismatches can create basis and cash-flow headaches. When dealers run tight on balance sheet or a coupon experiences concentrated demand, settlement conventions and timing can exaggerate moves.

How you access MBS exposure and how you hedge depends on scale, infrastructure, and risk appetite.

Direct institutional trading

Large desks trade TBAs, specified pools, and CMOs OTC. That requires dealer relationships, settlement operations, and repo facilities. Strategy choices include coupon selection (which coupon to own for convexity and carry), taking specified pools to harvest favourable prepayment profiles, and structuring CMO tranche exposure for timing or relative-value plays. When executing, dealers model cheapest-to-deliver and the expected delivery option value; arbitrageurs exploit mispricings between TBAs and the underlying cash market when funding is cheap and operational capacity exists.

ETF and mutual fund access

Retail and many institutional investors use ETFs or mutual funds that hold agency pass-throughs. ETFs provide liquidity and simple exposure to a coupon-weighted basket, but they compress the signals from specified pools and provide less control over financing and convexity management. The ETF wrapper removes most operational overhead at the cost of granularity.

Mortgage REITs

mREITs lever agency and non-agency MBS using repo. They attempt to earn net interest spread by borrowing short and holding longer-duration or lower-coupon MBS. This amplifies both returns and financing risk; when repo costs spike or MBS basis moves against them, equity holders can see volatile outcomes.

Hedging toolkit

Mortgage-based securities by using treasuries and interest-rate swaps. There are other ways to hedge your mortgage-based security but these are the easiest to use.

Practical hedging behaviour

Hedging MBS is dynamic. When rates drop, effective duration falls as prepayments accelerate, so traders trim duration hedges; when rates rise, effective duration increases, so traders add hedges. That dynamic creates transaction flow and margin friction, and in aggregate it can push prices—hedge demand is often the proximate cause of short-term MBS moves.

This article was last updated on: February 10, 2026